Kashmir: Mist of Magic and Haze of Hard Reality

Some memories have sharp edges when viewed up close, like tiles in a mosaic. Their meaning can be unclear. But as time creates distance between us and our experiences, a picture comes into focus and some of the sharp edges of those memories are smoothed over.

I’ve been thinking about this with respect to two trips I have taken to the Kashmir Valley, one sixteen years ago and the other just a few weeks passed. It’s easy for me to talk about the first trip. I’ve stepped back from the mosaic and a kind of picture has emerged. As for the latter, I will have to describe a few individual tiles see what emerges.

Magic of the past

My first visit to Kashmir was in April of 2008. I had an academic interest: I’d been teaching on a U.S. high school exchange program in nearby Ladakh. Our curriculum touched on Kashmir and the dispute over the region between India and Pakistan, into which the Kashmiri people were embroiled.

I didn’t expect that I could ignore lasting signs of the conflict during my visit – like India’s military presence – in favor of an illusory vision of a hidden paradise. And yet I admit that in addition to my studious interest I brought a touch of romanticization with me.

I had a bit of help. Along with my students I had recently read Salman Rushdie’s magical realistic spin on the Kashmir conflict, Shalimar the Clown, from which one may easily draw fantastic notions of the region, both bright and dark. I also love Led Zeppelin’s tune Kashmir, which (though written without any members of the band having visited the region) invites dreamy or even hallucinatory thoughts.

Checkpoints and Zoji-La

Our taxi departed Kargil, Ladakh at midnight that night back in 2008. We were bound for the precipitously winding road over Zoji-La, the Himalayan mountain pass connecting Ladakh and Kashmir. Our destination was Srinagar, the summer capital of Jammu and Kashmir. At the time J&K was an Indian state with special status and its own constitution. Today it is a union territory centrally administered from Delhi, which revoked the region’s special status in 2019.

Snow cutting vehicles had cleared the pass after heavy snowfall. Sometime during that dark, near-sleepless night in the back of the taxi I opened an eye to discover that we were driving between walls of snow twice the height of our vehicle. I tried to doze, looked out again and the strange image of the white snow wall repeated itself just a few feet from the window vibrating against my head.

Security is everywhere in Kashmir and Ladakh but there can be an informality to it that often constitutes the Indian bureaucracy. At some forgotten hour we pulled over at a checkpoint and entered a small, dimly lit room. A lone security officer was lying on a cot beside a still-burning hookah. After an unhurried puff of scented tobacco he entered our passport details into a battered notebook. A second puff and he wished us a safe journey while returning to a reclining position. Before long we reached another checkpoint and a similar scene ensued, like a recurring dream.

Dal Lake and Abdul

Through this dream my companion and I traveled by night, reaching the city at dawn. Our bags were not yet out of the jeep and on our shoulders when an auto rickshaw driver approached and we arranged transport to Dal Lake to see the floating vegetable market by shikara. I leaned back against the cushions, my mind a mist of fatigue from the night’s drive. The lapping of the lake against the boat was sedating. Vegetable sellers lifted burlap from products piled in their passing shikaras as if offering a glimpse at something forbidden. Thus the dream continued in the fog of the morning.

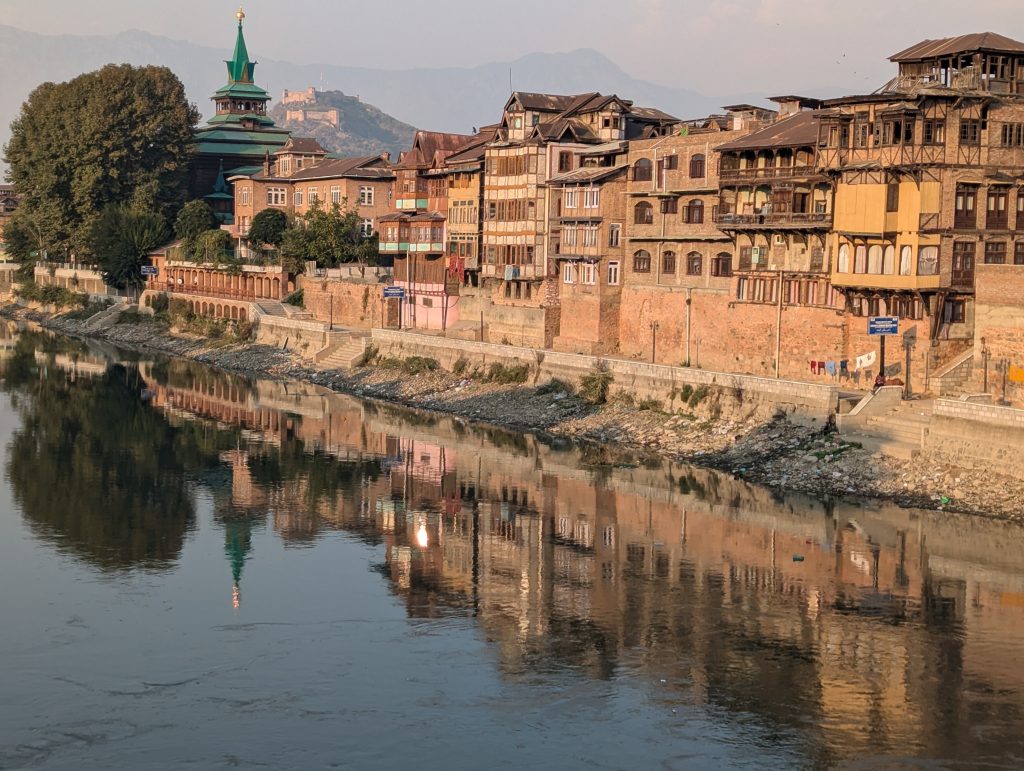

Dal Lake is the breathing spirit of Srinagar. As you leave the shore behind the city fades away. The surrounding mountains make themselves known beyond the lake’s fog and the city’s haze. Floating gardens and the vegetable market can still be found but as remnants of a bygone era when the lake was a busy trade center. Countless houseboats still offer accommodation for tourists seeking to fully experience life on the water, though this option means one is cut off from the rest of the city and must hire a boat to reach land as needed.

As we returned to land, Srinagar was awakening. We connected with Abdul, to whom we had been referred by a teaching colleague back in Ladakh. A self-styled guide with no formal business name at the time, he introduced us to the alleys of old Srinagar, bread bakers in smokey shops and buildings marred by the war just nine years passed. We shared aromatic Kashmiri tea on Abdul’s houseboat and lunch in his sister’s home. We visited the Shalimar gardens with his nephew, and received logistical help from his brother.

The Line of Control

We discussed the most recent period of unrest marked by the 1999 Kargil War. Tensions were on the rise leading up to that year. India and Pakistan had both recently conducted nuclear tests, while Kashmiri insurgency had been gaining traction throughout the 90s. Complicating matters was the fact that some Kashmiris sought independence while others favored accession to (and therefore received support from) Pakistan. In May of 1999 Pakistan sent troops across the Line of Control dividing Kashmir between India and Pakistan. This occurred on the Ladakhi side of the Zoji-La pass, in and near the town of Dras.

Ultimately India recaptured most of its land and saw an increase in patriotism, fueled in part by Indian media coverage and its sympathy for the military cause. Conspicuously missing from much of this coverage is how the conflict has affected the lives of everyday Kashmiris, who at the time saw a rapid increase in military spending in their homeland and a sharp drop in tourism income, and of course have long been at the center of a conflict they did not ask for.

The Kashmir conflict was born at the moment of the subcontinent’s 1947 Partition and the resulting birth of two states: India and Pakistan, which saw most Hindus settle in India and Muslims in Pakistan. At that time the Muslim-majority Kashmir had been ruled by a Hindu prince who sought to maintain independence rather than accede to either newly born state. But when raiders invaded from Pakistan he was all but forced into agreeing to accede to India in exchange for protection. Ultimately, with UN mediation, Kashmir would be bifurcated between the two states.

From this historical moment came multiple wars that would require a much deeper article to discuss but the reality of Kashmir since 1948 has been one of a land divided. A social reality stemming from the ensuing turmoil, per Sadaf Wani, is a kind of collective amnesia. “These traumatic events have effectively obscured the city’s pre-1947 identity from public consciousness.”1

I had a lot of facts swirling in mind from everything I’d read during my teaching assignment in Ladakh. The walk with Abdul brought much of this history to life. He brought us into conversation with locals for small glimpses of Kashmiri living while providing context on the socio-political reality through a wealth of anecdotes. I felt lucky to know such a person in a region that had until then had felt unreachable, or at least unknowable, due to its complicated recent history.

Pahalgam and forgotten departure

Our time was short but allowed for a visit to a valley close to Pahalgam in a more pastoral part of Kashmir. Memories that stand out from that side trip include declining a party invitation from the teenage son of our host. “He wants to show off the foreigners to his friends,” I recall our host saying with laughing skepticism. I remember a goat trying to headbutt us as we strolled down a dusty village road, as well as a long hike up through pine forest and our surprise in encountering numerous food vendors in a meadow. I remember cooling our feet in a frigid stream.

Beyond mystifying memories, time can also make them vanish. I have no recollection of our departure from Kashmir. But that’s where cut myself off. Saying that “a part of me never left Kashmir” would be romantic, but false. I did not remain like Abdul, who would continue to endure the hardships of life in a fractured frontier. Nor with millions of others who would experience that “precarious normalcy” as Sadaf Wani calls it, “a normalcy that is not sure of its own lifespan…”

I would not stay in that city where for many years armed military took up positions on street corners. I would not remain in Kashmir as the Hindu Nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party rose to power in Delhi and saw the Kashmiri people further ignored in the course of India’s development. Instead I would go about life, like many U.S.-born white men, with a world of opportunity at my doorstep and without that precarious normalcy that haunts so many lives across the world. Kashmir would be a snapshot for me to view at will, to reflect on fondly. A place to someday return at my convenience.

Reality of the present

That return visit to Kashmir would happen sixteen years later, in October of 2024. No longer a teacher, I did not bring the same level of academic interest, although the relative maturity of middle age and the responsibilities of parenthood probably added a seriousness to my frame of mind. Still, I couldn’t help but think that I might discover something I’d lost, hidden in the mist of sixteen years.

I did find certain things, some beautiful and others reminders of harsh realities, the kind we sometimes gloss over in our retellings. I will try not to do that here.

Approaching Kashmir

Our approach to Srinagar once again brought us by land. We had taken a short road-trip through Ladakh following a three-week stay in that region. This time we traveled by day and stopped more often to limit long stretches in the car for our daughter (and ourselves), and perhaps experience more along the way.

There was no snow this time, save for that which had just recently dusted some of the mountains. We did stop at a few vaguely familiar checkpoints. I couldn’t help but peek into a small building and derived some satisfaction in spotting a cot with a hookah beside it, as if no one had moved them since 2008. There was that same bureaucratic informality — the handwritten entry of our passport information into a worn notebook.

We descended the Zoji-La, appreciating the changing landscape, pine forest replacing the brown and arid mountains that define Ladakh. We noted the construction of a tunnel through the mountains, which will soon negate the crossing of the Zoji-La.

After descending from the pass, we made time for a brief visit to Sonamarg prior to reaching Srinagar. Sonarmag is a popular tourist destination with trekking and other outdoor activities nearby. Many visitors take a short horseback ride to behold nearby glaciers, depositing trash on the ground along the way. The word “Sonamarg” translates to “meadow of gold.” Sadly, though the mountain vistas are striking, the only gold to appreciate comes from shiny candy wrappers and potato chip bags that blanket the meadows.

For this reason, and because the horse handlers were quite aggressive with their sticks, we were happy that we wouldn’t be lingering. Thankfully, our daughter had been happily distracted with the simple pleasure of riding and enjoyed the horse excursion.

Call to prayer

Through a steadily increasing stream of traffic and honking we approached Srinagar, ultimately arriving in the Raj Bagh neighborhood. We’d rented a room there in the house of a local family. I noted the bed cover’s vivid green (sacred in Islam) and the ornate row of identical cabinets. One of them opened mysteriously into a large dressing and bathing area. I was surprised to find myself in such a quiet place in the midst of the city.

An exception to the quiet, as we would learn, was the system of megaphones mounted on the minaret of the mosque across the street. Certain sections of the islamic world have adopted the use of megaphones to project, far and wide, the five daily calls to prayer.

One night some years ago I laid awake listening to crickets through the window of our home near Baltimore. I noticed how their aggregate sound produced for me a soothing effect, while the lone cricket on a branch just outside my window did the exact opposite. Its solo chirping stood out as a singular annoyance against the otherwise enchanting chorus of the thousands. It was the same for me with the call to prayer as heard through a city of megaphones. The asynchronous chanting of so many prayers in the distance can be transporting, haunting and magical. As a person with strong values but not always strong habits I find gentle reminders of my convictions carried on the breeze to be a nice idea. But the megaphone aimed roughly at our window reframed that gentle reminder into a jarring one. Happily, it was so loud as to strike us as comical.

Reconnecting with Abdul

After settling in for a day it was time to reconnect with my old friend, Abdul, for a guided walk. Srinagar’s streets can be overwhelming and in this context Abdul’s guiding experience becomes clear. He glides through traffic, a cool bounce to his step, rarely missing a conversational beat. If you can keep up with Abdul’s walking and talking you will learn a great deal. Fortunately he hit the brakes on his Converse sneakers occasionally to accommodate our daughter, who was often on our shoulders.

Certain icons, like the Ghanta Ghar clock in Srinagar’s Lal Chowk neighborhood, rang a bell from that first trip in 2008. As we passed by that clock tower a driver bottomed out his car on a raised section of concrete. Comically, Abdul derived much pleasure and excitement from this. A crowd formed around the car within seconds.

We carried on. As we walked, we discussed Kashmir’s Sufism and the art and symbology distinguishing it from other forms of Islam. We talked about Kashmir and Ladakh and their political status within India, their semi-autonomy of the past and current movements towards the same (which are increasingly complicated within India’s current political climate).

At one point we visited a Hindu temple and sat on the floor of the shrine room for a moment’s rest. The temple’s caretaker inserted himself into the moment, advising us without context that it is only possible to achieve salvation within India, and that India’s Prime Minister since 2014, Narendra Modi, is Kashmir’s savior. In his opinion Kashmiris feel safer since Modi has been in power even if local election results suggest otherwise. “Safer from what?” I asked. He responded tentatively: “terrorism from Pakistan.”

Abdul once again introduced us to street vendors and friends he encountered along the way. Some of them were the same people I had briefly met many years before. They sold produce from the same cart parked on a corner or rosewater from the same dark and aromatic shop. We stopped numerous times, once at a tea stall, at another point enjoying a chochwor (a local form of bagel). Our daughter demonstrated surprising patience coming from a three-year-old subjected to a city tour filled with heavy, adult conversation.

Tourism in the Vale

Tourism (mostly domestic) is picking up again in Kashmir and Abdul has managed over 400 well-deserved, five-star Trip Advisor reviews. Srinagar’s economy now supports an increasing number of refined cafes and restaurants. There are plenty of guesthouses available in addition to the aforementioned houseboats.

Despite this fact we seemed to be some of the only non-Indian tourists around. I asked a number of locals if they’ve seen any other visitors from the U.S. Mostly they laughed or replied with a simple “no.” “A few Europeans,” one local said, but “no Americans.” For this reason we drew quite a bit of curiosity, and in at least one instance a kind of judgment when a driver asked me why the U.S. wasn’t doing more to protect Palestinians.

Kashmir can be challenging for a western tourist. The term “culture shock” is thrown around but that “shock” is often the cumulative effect of many little things. Locals may be accustomed to them but they can be difficult for foreigners. To describe these small difficulties will feel trivial, perhaps even snobbish, but they are part of the mosaic, the tiles whose edges still appear sharp.

Some challenges of being a westerner in Kashmir

For example, although we knew the correct fares from previous rides, many auto rickshaw drivers engaged us in what felt like unnecessarily complicated negotiations over price. This was probably in part simple habit or local custom. But we knew that in seeing foreigners, at least some drivers saw an opportunity to make a few extra rupees.

We had difficulty communicating the concept of “zero” spice in restaurant orders, a precaution we took since, though we like our food a bit spicy, our daughter does not. The Indian palate tolerates spice to a degree that most Americans do not comprehend. Certain local meals come with a small bowl of curd to balance or tone down the spice. It’s a nice thing to have but not a sufficient spice-mitigator for our sensitive palates!

There is the aforementioned trash. Once I saw a park attendant extend a hand from his kiosk window to drop several wrappers onto the grass, which was already aglow with wrappers shimmering in the sun. In Indian cities it is often possible to smell trash being burned. (At one point someone clarified that some of the smell and haze comes from farmers burning fields after a harvest.)

I found the noise pollution particularly challenging (I do at home too, I should note). Honking at each corner and in between is a courtesy or precaution that many drivers exercise on roads throughout South Asia and is not limited to Kashmir. Stop signs are somewhat rare, leaving pedestrians to exercise a combination of faith and skill when crossing roads.

Using local forms of transportation can be challenging for foreigners. In our case there was an overly complicated ride to Pahalgam. During our walk, Abdul had repeatedly urged us to forgo the 30 USD cost of a private taxi to get door-to-door from our guesthouse in Srinagar to our destination just three hours away in the Aru Valley. He encouraged us to instead use a series of shared taxis, which could have cost about 6 USD for a four-hour trip. Between the initial auto rickshaw to the taxi stand, waiting for passengers to come along and fill empty seats, and being directed to the wrong depot for the final leg, our trip took most of the day. And since we twice agreed to pay extra to cover the cost of empty seats rather than continuing to wait, and because we paid for Vienna to have her own seat rather than hold her on our lap (as any local would have done), the trip cost roughly 15 USD.

A local might not think much of waiting longer to reach their destination. This is especially true when the alternative could mean spending the equivalent of a day’s wages. “Subjecting ourselves” to a longer trip was more about gaining insight into local life, as opposed to the savings. And yet, Abdul’s recommendation was more in consideration for the money we’d save, a consideration we should remember and appreciate.

We reached the Aru Valley and enjoyed our short hikes up into the pine forests. Clean air and little sound. The litter only reached as far as most tourists venture, which is not far. Hike high enough and it’s only pines, clear streams and the occasional cow or goat. We sat by a massive, fallen tree and Vienna pretended to make soup with pine needles.

The mist

It’s hard to know what will stand out from the mist of our recent trip after another sixteen years have gone by. Certainly I will remember Abdul tying historical threads together even while weaving through traffic. We met a musician-cafe owner who suggested a future, remote collaboration on a song. If that happens, he will no doubt stand out in my memory. I’ll remember Vienna’s happy moments at the playground in Srinagar, learning to climb, pretending to be afraid of a slide and then sliding, oblivious to the actual fear that so many Kashmiris have known. I’ll remember the absurd comedy in the existence of the occasional traffic light, to which no one pays the slightest attention. I will remember the spice, and icy stares that masked hidden kindnesses.

I will probably remember some of the small annoyances of being a foreigner in Kashmir, those individual crickets chirping in my ear. But perhaps the distance of the past will be more like that distant chorus of crickets, calls to prayer coming through our window from faraway corners of the city. Or like the fog of Dal Lake. The fog that is also a haze from the city and farm fields burning, all of it swirling together to veil the mountains of Kashmir.

- Wani, Sadaf. City as Memory: A Short Biography of Srinagar. Aleph Book Company, 2024. ↩︎